Adoption and Mental Health

Children who are adopted often have a history of abuse, neglect, and trauma. Adoptive parents may not know all the details before the adoption, but as the children become more comfortable with their new families, they share many details of their lives. The general perception is that neglect doesn’t involve physical or sexual abuse and is not as damaging. But when the caregiver does not meet a child’s needs, that is also a form of abuse, and the emotional outcome is equally detrimental.

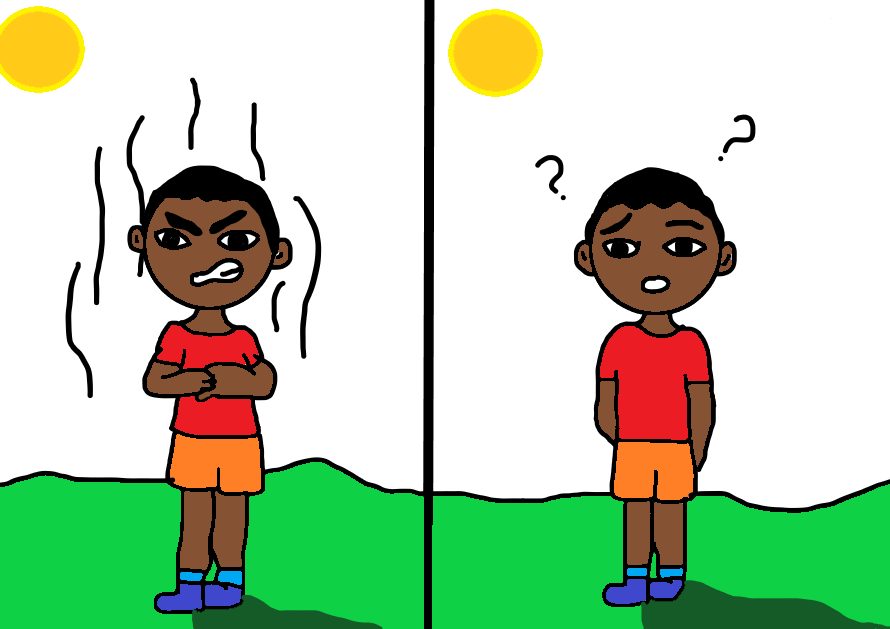

For many adopted children, abuse is not a one-time experience. The combined effect of all their traumatic experiences results in complex emotional needs. What do parents see outwardly? Challenging behaviours! To manage the behaviours, parents must address their children’s underlying mental health needs. It is not a quick process, nor is it one size fits all.

What can you do if you suspect that your child’s challenging behaviours mask a developing mental health disorder?

Seek help early. We Indians have many preconceived notions about seeking professional support for mental health needs and put it off until the problem becomes unavoidable. But if we get help early for mental health problems, it can make a big difference and prevent other complications.

What should you do?

Note down the behaviours, when they began, and their frequency. These notes will come in handy when you meet with professionals.

Consult a child psychiatrist with all the information about the child’s history, current performance, and concerns. That period when we recognize that we need help is not only stressful; it is also confusing and emotionally demanding. It is easier to accept suggestions from someone who is not part of the day-to-day challenges, someone who is trained to guide us in such situations.

The psychiatrist may prescribe medications. Keep an open mind about giving your child medications. Children who struggle with anxiety, PTSD, or any other mental health disorders are overwhelmed by the demands of their illness. Indian society emphasizes developing a strong will to overcome hardship. Parents would rather have their children engage in coping strategies like yoga and meditation. Yes, these are excellent strategies, but children may need medication to bring them to a place to do yoga or meditation. Understanding how these strategies are beneficial takes time and maturity.

Medication usually starts at a low dosage to check for side effects. Did the psychiatrist explain the side effects? Will there be changes in diet, sleep patterns? Some medications may have rare but severe side effects. The doctor will increase the dosage until it reaches the therapeutic dose. That’s when you can see an impact on the symptoms to see if the medicine works or not. If it is not effective, go back to the psychiatrist and follow up with a different medication.

Consult a licensed therapist. The therapist is the safe person to whom children can share anything they want, even about their adoptive parents. They can process their life events and learn how to take care of themselves. A licensed therapist is trained to identify and address the issues that result from trauma and guide their clients to learn self-help skills. As kids process the traumatic incidents of their lives, they show more challenging behaviours.

You may think that therapy is not helping your children. At such times, motivational speakers, alternative healers, and parenting guides look attractive because their messages sound positive, and healing seems quicker. It is okay if you want to try other approaches along with therapy. Just make sure that their approach doesn’t contradict what the therapist says.

For instance, many parenting guides talk about how ADHD is not an actual condition and is all in your mind. Or how trauma is erased by focusing on the positive aspects of adoption. These questionable practices make adults feel good because it sounds like an official sanction to deny that a problem exists. But ignoring or denying the underlying mental health condition does nothing to resolve the difficulties that stem from it. If your child is not comfortable with the first therapist, find another. The client-therapist rapport is essential for the child to share and learn new skills.

Inform your children about why you seek help from professionals. If you hide that they are seeing a psychiatrist or a counselor, children will internalize the stigma when they find out. Explain to them that their past experiences create both stress and intense emotions, and the role of the professionals is to guide children to manage these.

Our children are clear communicators. When we talked to them about going to therapy, their voiced their fears. “Are you sending us there because you think there is something wrong with us? Does that mean you will send us back?” We had to reassure them that we weren’t using therapy as an excuse to find fault with them. We pointed out that they were under a lot of stress because they had to learn so many things at home and school. They could tell their therapist whatever they wanted, and she would not share any of it without their permission.

The girls were smart enough to google and learn more about therapy and counseling. Our oldest challenged us for many months. “Why do you think I have a mental health problem? Do you think you don’t have any? Do you think other kids don’t have any problems at all?” We answered her honestly. She had experienced an enormous loss when she lost her birth mother and cared for her siblings. It was a lot for someone so young. She retorted, “Yes, so don’t you think it is natural for me to feel this anger?” We validated her concerns, and our discussions progressed over weeks until she started noticing changes.

Eventually, the oldest acknowledged that therapy did help her recollect more details from her childhood and taught her to manage her emotions when the memories surfaced at different times. With our second child, it was a different path. She loved talking to someone who didn’t have the same rules, who didn’t have any demands on her. This child would cry or spin tales to cover up her actions because she was afraid of the consequences. Eventually, she learned to trust us and own up to some complex behaviours.

The children’s academic performance improved as their emotional state stabilized. They completed their homework, turned in their assignments on time, and prepared for class tests. They still need help, but their attitude towards learning has improved tremendously.

Involve your children in activities that help others. Adopted children have always been at the receiving end. Giving to others taps into their feelings of compassion and shows them that they can change the circumstances for others, however small it may be. They develop a sense of purpose even when they are struggling.

Acknowledge your children’s resiliency. In their struggle to understand the circumstances that led to the adoption, children often wonder if something about them made their parents let go. As a result, they grapple with poor self-esteem and do not see themselves as brave or resilient. But surviving in their circumstances at such a young age shows tremendous courage.

When we found out that our oldest daughter had witnessed a murder, my mother’s remark made my daughter think differently about herself. “At such a young age, she has shown so much presence of mind and courage by pretending to sleep!” That comment made her rethink her responses since it came from someone other than her father and me. “You know, I never thought about myself that way.” Adopted children have to put themselves out there, learning many skills much later than their peers. Bring it to their attention that putting in the effort to learn something takes courage.

Provide opportunities to develop children’s talents. Give them feedback so they can see their progress. “Last year, you needed help to write an essay. This year you can write the essay on your own.” Children need to see that they are capable, have ambitions, and work to meet the goals, even if they struggle in other areas.

Model healthy practices. Adopted children may have had routines in their institutions but don’t understand how a nutritious diet, physical activity, and sleep foster positive mental health. Our daughters remark that it is bizarre that they must go to bed at a particular time. They woke up very early at the institution to do chores and pray. Interestingly dinner was late, and so was bedtime.

It was a cultural shift when we talked about getting enough sleep and not having tea or coffee until they were older. When they saw me exercise at home during the pandemic, they couldn’t understand why I would do such a thing. But watching us take care of ourselves teaches them that they too can take charge of their health when they are older.

Take care of yourself and other family members. When a child has a mental health disorder, the entire family struggles. The stress of finding the right help and seeing progress can overpower parents. Take time to do things for yourself. If you have other children, be aware of their needs so that they don’t fall through the cracks.

Learn more on how trauma affects a child’s growing brain here.

Other episodes in this series:

Educational Needs of Adopted Children

Children’s Life experiences Before Adoption